1 Introduction

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

2.2 Preparation of CN

2.3 Preparation of X%CN/BiOBr

2.4 Preparation of X%CN/OVs-BWO

OVs-BWO, 30%CN/OVs-BWO, 50%CN/OVs-BWO and 60%CN/OVs-BWO were also prepared by using 20%CN/BiOBr, 30%CN/BiOBr, 50%CN/BiOBr and 60%CN/BiOBr as precursors, respectively.

2.5 Measurement of photocatalytic CO2 reduction activity

2.6 In situ EPR characterization

2.7 In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy

2.8 Computational details

3 Results and discussion

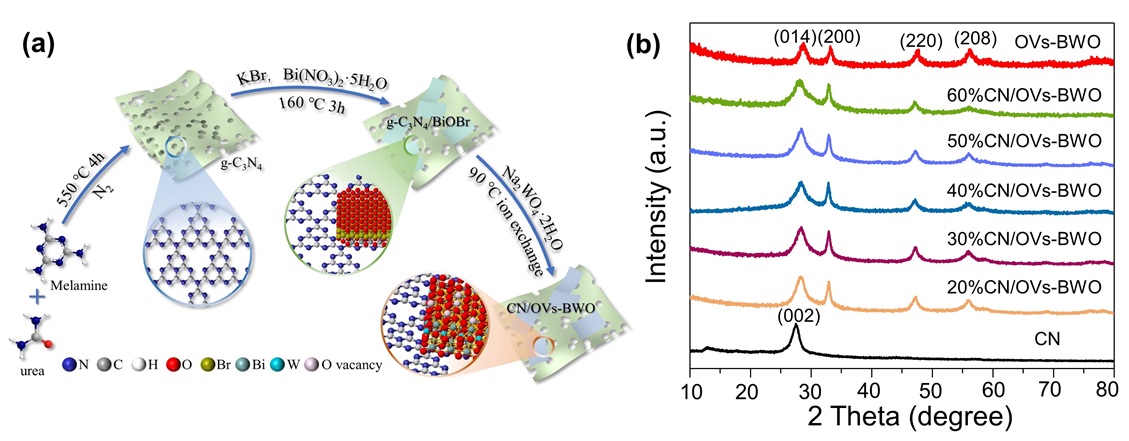

Figure 1. (a) Schematic illustration for the preparation procedure of the CN/OVs-BWO. (b) XRD patterns of the prepared samples. |

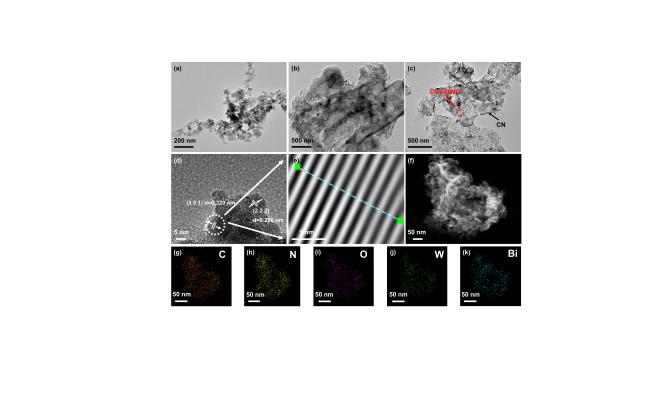

810 cm−1 is attributed to the vibrational properties of the tri-s-triazine heterocycles of CN[51-53]. In addition, the peaks at the 1200-1650 cm−1 region are assigned to the different stretching vibration modes of the C-N bond. The N-H stretching of amino groups and O-H stretching of hydroxyl groups appeared in the 3000-3500 cm−1 region. As revealed by the TEM image (Figure 2a), OVs-BWO demonstrates a 2D flake structure (see also SEM image in Figure S3a), which is beneficial for its coupling with the 2D CN (Figure 2b and Figure S3b) to form a 2D-2D structure[54]. For the CN/OVs-BWO, numerous nanoflakes are found to be uniformly distributed on the CN nanosheet (Figure 2c and Figure S3c). Based on the IFFT images, these nanoflakes show an interplanar spacing of 0.329 nm (Figure 2d and e), corresponding to the (351) plane of OVs-BWO. Furthermore, according to the elemental mapping images shown in Figure 2f-k, the Bi, W, C, N, and O elements are homogeneously distributed on the CN/OVs-BWO, suggesting the presence of both CN and BWO.

Figure 2. (a-c) TEM images of OVs-BWO (a), CN (b), 40%CN/OVs-BWO (c). (d-k) HRTEM image (d), lattice spacing (e), SEM image (f) and elemental mapping images (g-k) of 40%CN/OVs-BWO. |

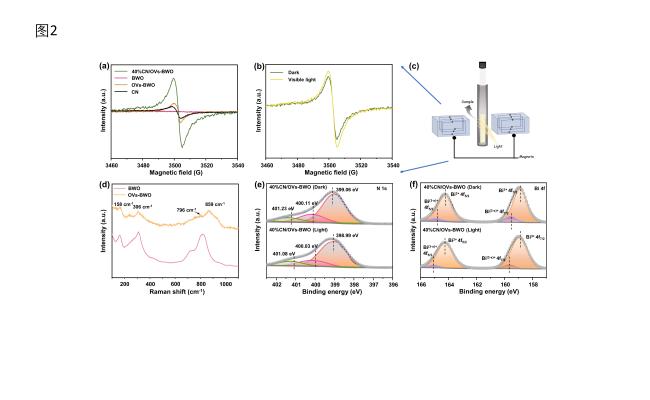

Figure 3. (a) Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra of CN, OVs-BWO, BWO and 40%CN/OVs-BWO. (b) In situ EPR spectra of 40%CN/OVs-BWO under dark and visible light irradiation conditions. (c) Schematic illustration for the configuration of in situ EPR system. (d) Raman spectra of samples of OVs-BWO and BWO. (e, f) ISI-XPS curves of N 1s (e) and Bi 4f (f). |

(43.48 m2/g). In addition, after the introduction of the oxygen vacancies on the prepared samples (i.e., OVs-BWO (58.79 m2/g) and 40%CN/OVs-BWO (56.32 m2/g)), their specific surface areas greatly increase, suggesting that the oxygen vacancies can endow enormous surface active sites on BWO.

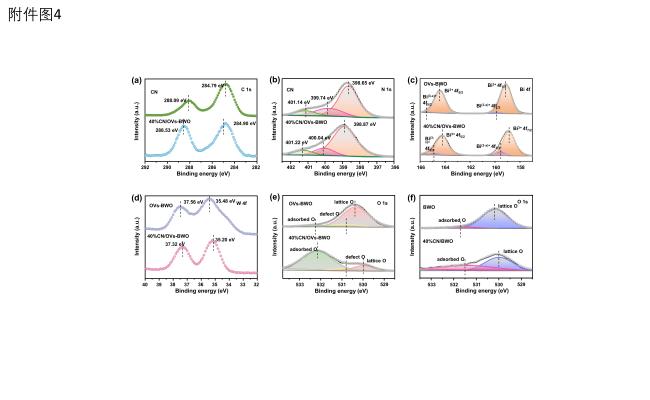

Figure 4. (a-e) High-resolution (a) C 1s, (b) N 1s, (c) Bi 4f, (d) W 4f and (e) O 1s XPS spectra of CN, OVs-BWO and 40%CN/OVs-BWO. (f) High-resolution O 1s XPS spectra of BWO and 40%CN/BWO. |

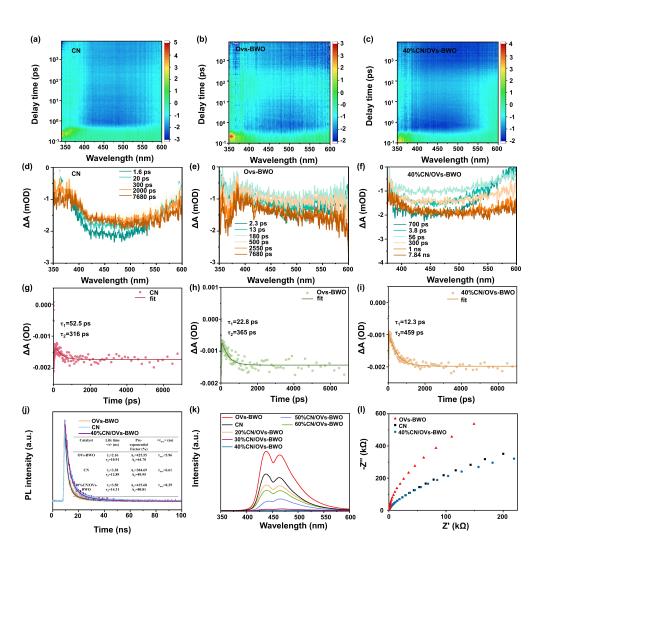

Figure 5. The pseudocolor plots of (a) CN, (b) Ovs-BWO and (c) 40%CN/OVs-BWO. Transient absorption spectra (d) CN, (e) Ovs-BWO and (f) 40%CN/OVs-BWO.The corresponding fs-TAS decay curves (at 500 nm) for (g) CN, (h) Ovs-BWO and (i) 40%CN/OVs-BWO photocatalysts. (j) Time-resolved PL spectra of theindividual photocatalysts. (k) PL spectra of CN, OVs-BWO and CN/OVs-BWO loaded with different CN contents. (l) EIS Nyquist plots of CN, OVs-BWO and 40%CN/OVs-BWO. |

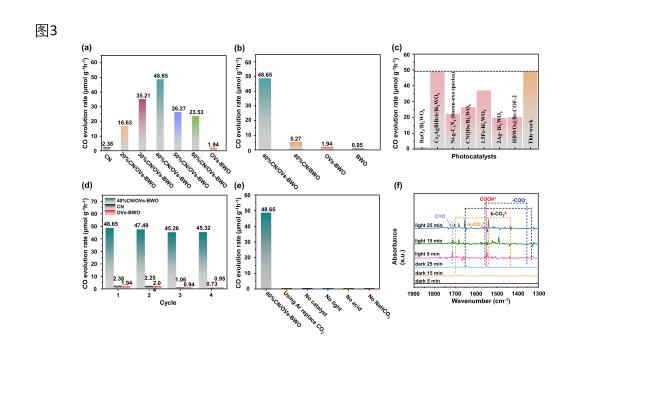

48.65 μmol h−1g−1 among all the prepared samples, which is ca. 20 times and 25 times higher than the CO production rate of CN (2.38 μmol h−1g−1) and OVs-BWO, respectively. More interestingly, the CO production rate of 40%CN/OVs-BWO is about

9.23 times higher than that of 40%CN/BWO

(5.27 μmol h−1g−1), implying the synergistic effect between the oxygen vacancies on BWO and heterojunction formed between OVs-BWO and CN. The AQY value generated by CO on 40%CN/OVs-BWO is 0.1145%. Such a CO production rate is also exceeding most of the photocatalytic CO2 conversion performance of recently reported photocatalytic systems for CO production (Table S1, Figure 6c). It can be clearly shown in Figure S9 that there is a linear relationship between time and CO2 reduction process CO yield. No obvious decrease in photocatalytic CO2 conversion performance can be observed over 40%CN/OVs-BWO for four cycles of recycling test (Figure 6d). In addition, the XRD characterization indicates that the phase structure of the 40%CN/OVs-BWO does not alter after the recycling test, implying its high photostability (Figure S10). Control experiments shown in Figure 6e further prove that light and photocatalysts are indispensable aspects of photocatalytic CO2 conversion. CO production can hardly be detected when performing the photocatalytic CO2 conversion test in the dark, without catalyst and without CO2 conditions.

Figure 6. (a) Comparison of the photocatalytic CO2 conversion performance of the CN/OVs-BWO with different CN loading contents for CO production. (b) Comparison of the photocatalytic CO2 conversion performance of the CN, BWO, OVs-BWO and CN/OVs-BWO for CO production. (c) Comparison of the photocatalytic CO2 conversion of the 40%CN/OVs-BWO with the previously reported photocatalysts. (d) Recycling photocatalytic CO2 conversion tests over CN, OVs-BWO and CN/OVs-BWO. (e) CO2 photocatalytic activity under varied conditions. (f) In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectra for photocatalytic CO2 conversion over 40%CN/OVs-BWO. |

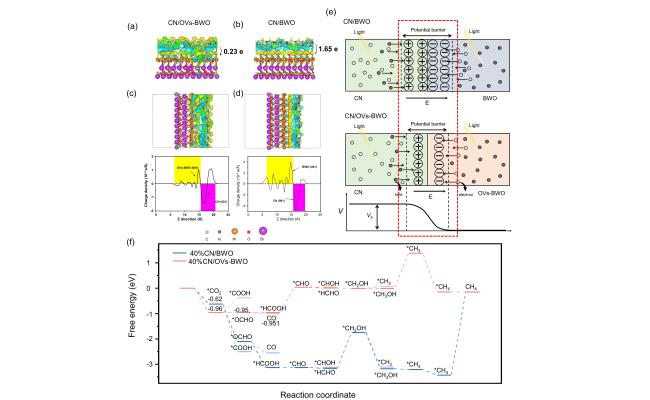

Figure 7. (a, b) Side view of CN/OVs-BWO (a) and CN/BWO (b). (c, d) Bader charges analysis atoms of the isosurface of CN/OVs-BWO (c) and CN/BWO (d). (e) Schematic illustration of the shrinkage of the potential barrier of CN/OVs-BWO compared to that of the CN/BWO. Vb and E indicate potential barrier and electric field, respectively. (f) Gibbsfree energy profiles for CO2 photoreduction on CN/OVs-BWO and CN/BWO. |