1 Introduction

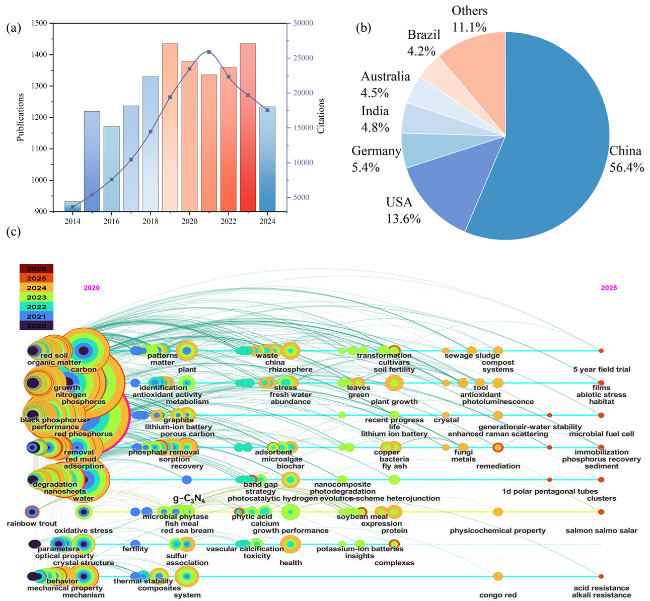

Fig. 1 (a) Number of citations and publications in Web of Science over time. (b) Percentage of publications from different countries. (c) Using “red phosphorus” as the key “title word”, set “publication year”, and search the “Web of Science” database to find out the evolution of the number of records of the literature published from 2020 to 2025. |

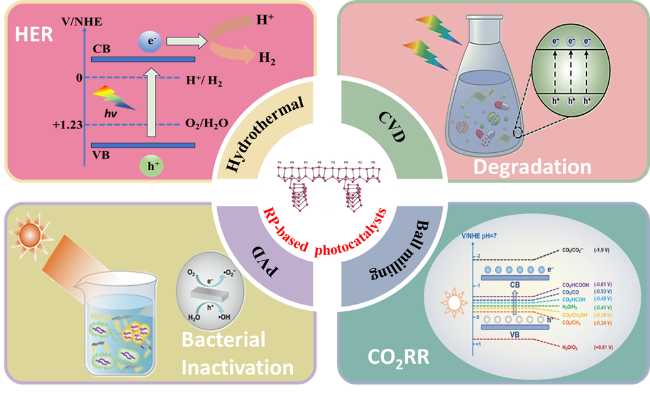

in photocatalysis using elemental RP-based materials (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Synthesis and photocatalytic applications of RP-based photocatalysts. |

2 Structure properties of RP

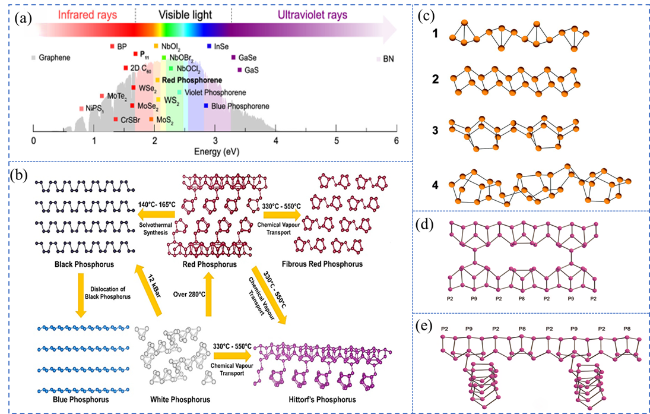

2.1 Types and chemical structures of RP

Fig. 3 (a) The absorption of light by RP and other 2D materials. Reproduced with promission. (b) Atomic structure of different P allotropes and the associated synthesis conditions. Reproduced with promission. (c) Four probable structural subunits of ARP. Reproduced with promission. Proposed atomic structure of (d) fibrous RP and (e) Hittorf’s P. (a) is adapted with permission from ref. 60 (Copyright 2020, Royal Society of Chemistry); (b) is reproduced with permission from ref. 22 (Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society); (c) is reproduced with permission from ref. 63 (Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH); (d and e) are reproduced with permission from ref. 52 (Copyright 2010, American Chemical Society). |

2.2 Electronic structures of RP

3 Synthesis strategies of RP-based photocatalysts

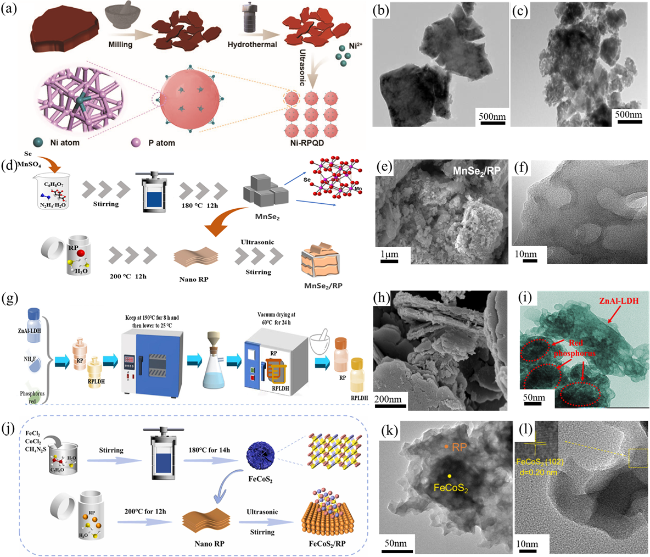

3.1 Hydrothermal

3.2 Ball milling

Fig. 4 (a) The hydrothermal synthesis strategy for Ni-RPQD photocatalysts. TEM images of (b) bulk RP and (c) hydrothermal RP. Reproduced with promission. (d) The hydrothermal synthesis strategy for MnSe2/RP photocatalysts. SEM image (e) and TEM (f) of 10 wt % MnSe2/RP. Reproduced with promission. (g) The hydrothermal synthesis strategy for RPLDH photocatalysts. SEM image (h) and TEM (i) of RPLDH0.8. Reproduced with promission. (j) The hydrothermal synthesis strategy for FeCoS2/RP. SEM image (k) and TEM image (l) of FeCoS2/RP. Reproduced with promission. (a-c) are adapted with permission from ref. 85 (Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH); (d-f) are reproduced with permission from ref. 86 (Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society); (g-i) are reproduced with permission from ref. 87 (Copyright 2023, Elsevier); and (j-l) are reproduced with permission from ref. 88 (Copyright 2023, Elsevier.) |

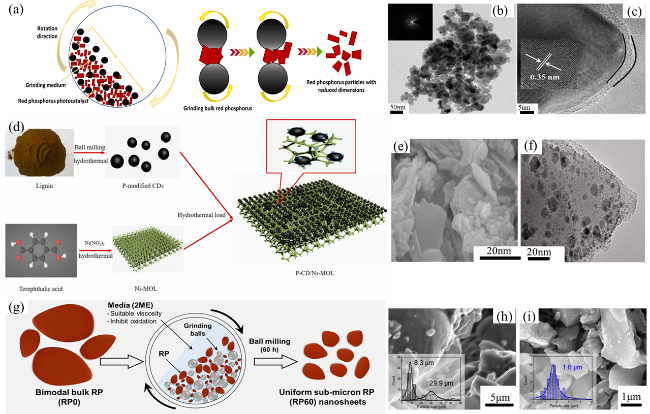

(Fig. 5a-c) [22]. This approach presents a cost-effective and scalable alternative to plasmonic metals for visible-light-driven applications, offering significant potential for the development of advanced photocatalytic systems.

Fig. 5 (a) Ball milling synthesis strategy. (b) TEM image and (c) HR-TEM image of the RP-TiO2-12h. Reproduced with promission. (d) The schematic diagram of synthetic route. (e) SEM image and (f) HR-TEM image of the P(1.0)-CD/Ni-MOL. Reproduced with promission. (g) Ball milling synthesis strategy. SEM images of (h) RP30, and (i) RP60. Reproduced with promission. (a-c) are adapted with permission from ref. 22, 94 (Copyright 2022, 2016, American Chemical Society, Science); (d-f) are reproduced with permission from ref. 95 (Copyright 2022, Elsevier); and (g-i) are reproduced with permission from ref. 96 (Copyright 2023, Elsevier). |

(Fig. 5g-i) [96]. Their results revealed that the optimized RP60 exhibited a defect-rich nanosheet structure, which significantly enhanced its photothermal performance. Further improvements in solar steam generation were achieved by incorporating a porous polyurethane support and plasmonic resonance-heating silver nanoparticles, thereby maximizing light absorption and heat localization. Despite these advancements, challenges persist in ensuring the long-term stability, high-temperature durability, and cost-effectiveness of these materials. Future research should focus on optimizing structural design and material integration to achieve a balance between efficiency, stability, and economic viability for large-scale applications.

3.3 PVD

3.4 CVD

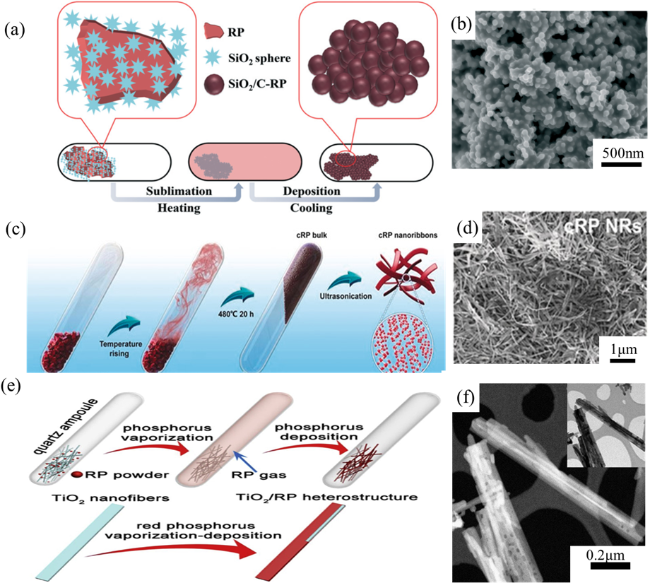

Fig. 6 (a) Schematic illustration for the preparation of SiO2/C-RP. (b) SEM image of SiO2/C-RP. (c) Synthesis of CRP bulk and nanoribbons. (d) SEM images of CRP NRs. (e) Schematic illustration for the preparation of TiO2/RP. (f) STEM image of TiO2/RP. (a and b) are adapted with permission from ref. 100 (Copyright 2020, Royal Society of Chemistry); (c and d) are reproduced with permission from ref. 101 (Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH); and (e and f) are reproduced with permission from ref. 102 (Copyright 2019, Elsevier). |

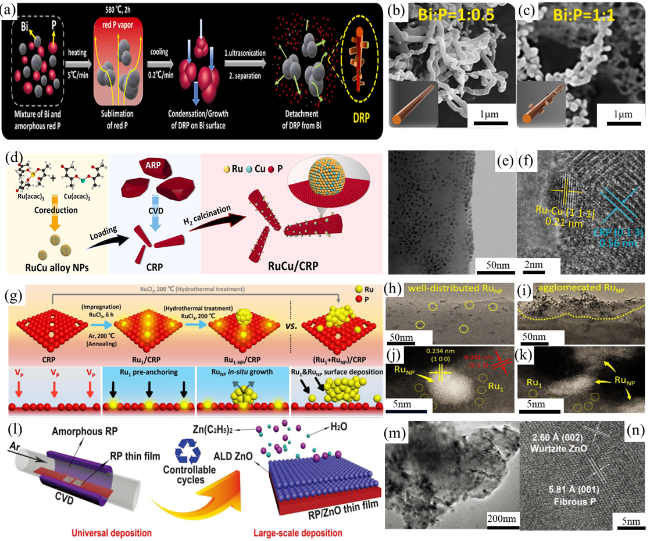

Fig. 7 (a) The CVD synthetic procedure of the DRP products. SEM images of (b-c) DRP. Reproduced with promission. (d) Schematic synthesis strategy of RuCu/CRP. TEM image (e) and HR-TEM image (f) of RuCu/CRP. Reproduced with promission. (g) Schematic synthesis strategy of Ru1/CRP, Ru1-NP/CRP, and (Ru1+RuNP)/CRP. TEM images of (h) Ru1-NP/CRP, and (i) (Ru1+RuNP)/CRP. HAADF-STEM images of (j) Ru1-NP/CRP, and (k) (Ru1+RuNP)/CRP. Reproduced with promission. (l) Schematic synthesis strategy of RP/ZnO. TEM images of (m) and HR-TEM image (n) of Ti-RP/ZnO. Reproduced with promission. (a-c) are adapted with permission from ref. 110 (Copyright 2022, Elsevier); (d-f) are reproduced with permission from ref. 111 (Copyright 2024, Elsevier); (g-k) are reproduced with permission from ref. 112 (Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH); and (l-n) are reproduced with permission from ref.113 (Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH). |

4 Structural characterization techniques of RP-based photocatalysts

4.1 AFM

4.2 KPFM

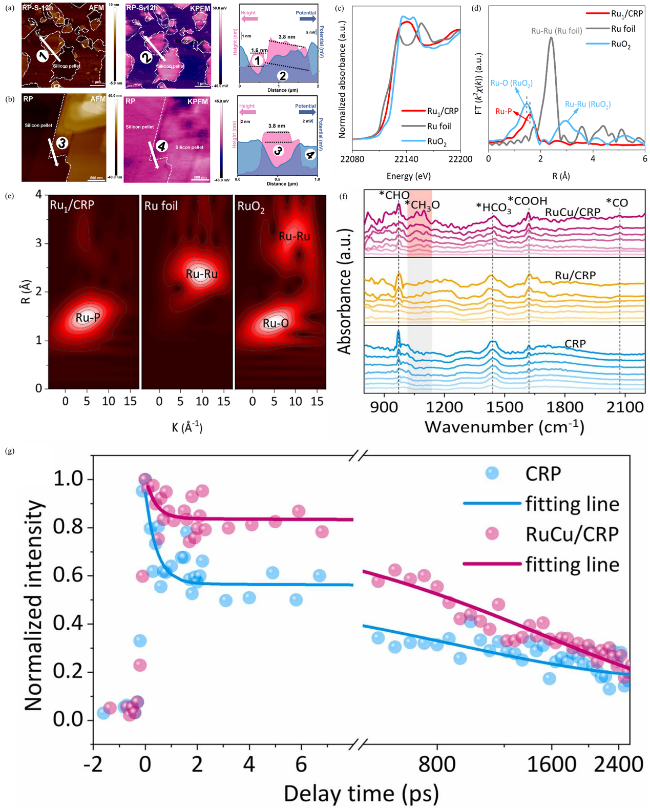

(Fig 8b) to examine the electron transfer dynamics between bulk RP and RP nanosheets (RP NS) [148]. AFM images revealed structural differences between bulk RP and RP NS, confirming the formation of a composite structure with distinct surface morphologies. KPFM measurements indicated a potential difference between the two forms of RP, with the ultra-thin RP nanosheets exhibiting a lower potential than the bulk RP. This potential difference facilitated the transfer of photogenerated electrons from bulk RP to RP nanosheets, which was critical for enhancing photocatalytic performance. The optimized energy band structure and surface potential at the interface effectively promoted electron migration, leading to an improved hydrogen production rate and stability over multiple cycles. Thus, AFM and KPFM not only confirmed the structural features but also provided direct evidence of the electron interactions that play a crucial role in enhancing photocatalytic performance.

Fig. 8 AFM images, KPFM images (a) RP-S-12 h and (b) bulk RP. Reproduced with promission. (c) Ru K-edge XANES profile, (d) Fourier-transform EXAFS spectra in R space, and (e) wavelet transform EXAFS spectra of Ru1/CRP, Ru foil, and RuO2. Reproduced with promission. (f) in-situ DRIFTS spectra of the CRP, Ru/CRP, and RuCu/CRP samples. (g) Normalized fs-TA decay kinetics plots with exponential fitting curves of CRP and RuCu/CRP probed at 650 nm under 343 nm laser excitation. Reproduced with promission. (a and b) are adapted with permission from ref. 148 (Copyright 2022, Elsevier); (c-e) are reproduced with permission from ref. 112 (Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH); and (f and g) are reproduced with permission from ref.111 (Copyright 2024 Elsevier). |

4.3 XANES

4.4 EXAFS

4.5 in-situ DRIFTS

4.6 fs-TA

(Fig. 8f-g) [111]. The fs-TA measurements revealed the process of charge carrier migration, indicating that the incorporation of RuCu alloy effectively extended the lifetime of charge carriers and reduced charge recombination. This prolonged charge lifetime played a decisive role in enhancing photocatalytic activity, thus promoting CH4 generation. Meanwhile, in-situ DRIFTS analysis identified the key intermediates formed during the CO2 reduction process, further showing that the addition of Cu altered the reaction pathway and facilitated the formation of *CH3O, a critical intermediate for CH4 synthesis. By combining these two characterization techniques, the study verified the synergistic effect of the RuCu alloy, optimizing charge carrier separation, improving reaction efficiency, and steering the CO2 reduction process toward the CH4 synthesis pathway, significantly surpassing the performance of current elemental phosphorus-based photocatalysts.

5 Theoretical simulations

5.1 Electronic structure calculations

5.2 Optical absorption and photoresponse analysis

5.3 Interface and heterojunction simulations

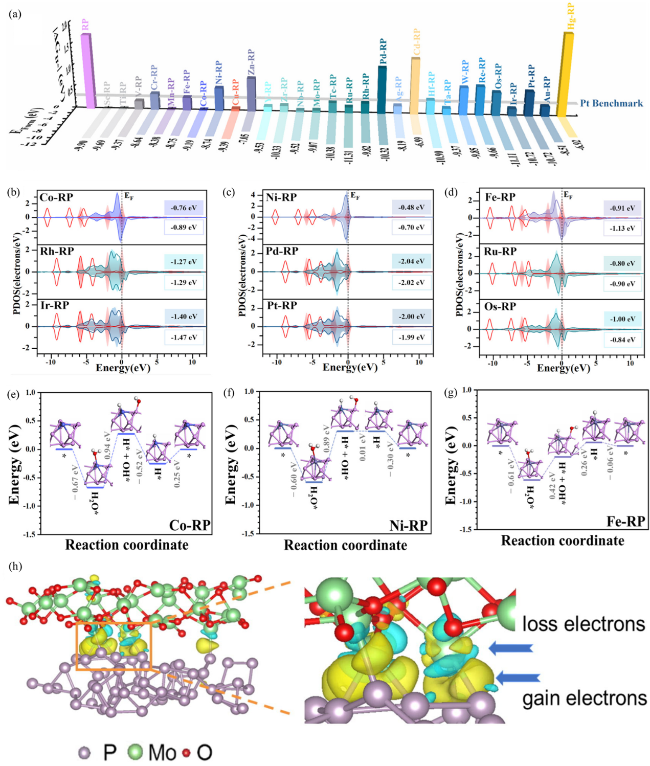

Fig. 9 (a) The cube columns represent |ΔGH*|, and the shadows indicate the corresponding formation energy (EForm) of pristine RP and 29 types of TM-RP SACs. (b-d) The d-band center positions of TM-RP before (color-filled) and after (color-framed) H2O adsorption calculated via density of states (DOS). The reaction energy changes of the key steps in the HER during water splitting on (e) Co-RP, (f) Ni-RP and (g) Fe-RP. Reproduced with promission. (h) Charge difference map of P-MoO2 and P-MoO2-CO2. Reproduced with promission. (a-g) are adapted with permission from ref. 180 (Copyright 2024, Royal Society of Chemistry), and (h) is reproduced with permission from ref.181 (Copyright 2025 Elsevier). |

6 Applications of RP in photocatalysis

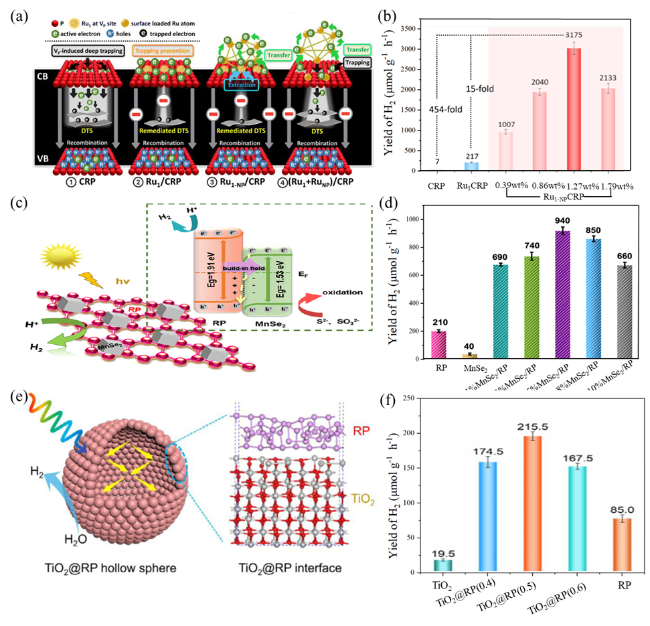

6.1 Photocatalytic for hydrogen production

Fig. 10 (a) Schematic illustration of the proposed charge dynamics. (b)Visible light PHE rates of CRP, Ru1/CRP, and the Ru1-NP/CRP samples with different Ru contents. Reproduced with promission. (c) Schematic illustration of the proposed charge dynamics. (d) Rates of pure RP, pure MnSe2, and x wt % MnSe2/RP. Reproduced with promission. (e) Suggested mechanism for photocatalytic hydrogen generation using TiO2@RP. (f) Photocatalytic hydrogen production activities. Reproduced with promission. (a and b) are adapted with permission from ref. 112 (Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH); (c and d) are reproduced with permission from ref. 86 (Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society); and (e and f) are reproduced with permission from ref.201 (Copyright 2022, Elsevier). |

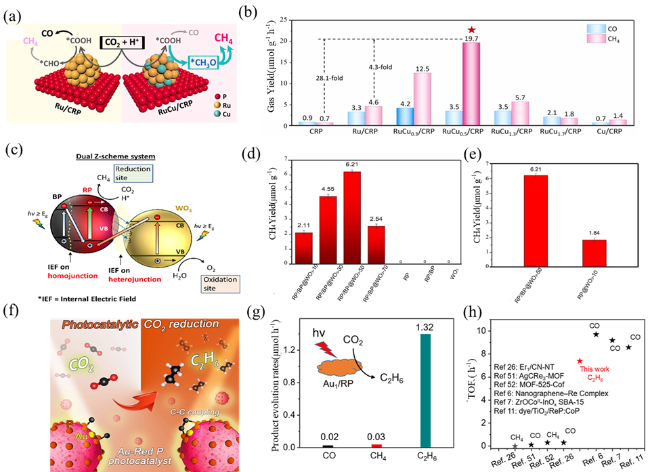

6.2 Photocatalytic for CO2 reduction

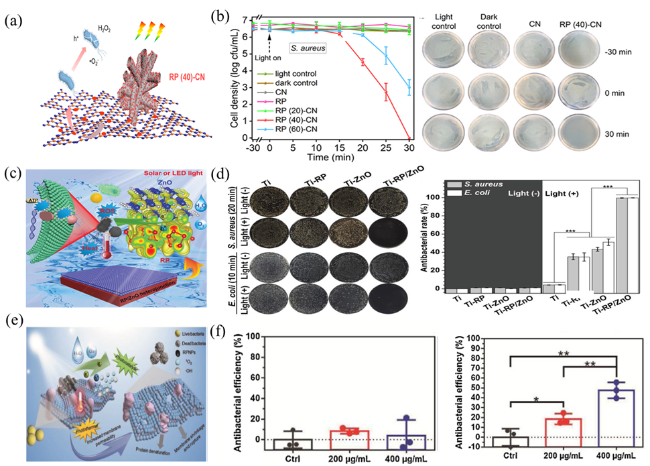

6.3 Photocatalytic bacterial disinfection

Fig. 11 (a) Proposed reaction mechanism for photocatalytic CO2 reduction reaction processes over Ru/CRP and RuCu/CRP. (b) The production yield rates of CO and CH4 in various photocatalysts under solar light irradiation. Reproduced with promission. (c) Mechanism diagram of photocatalytic reduction of CO2 by RP/BP@WO3. (d) Total photocatalytic CH4 yield achieved by RP/BP@WO3-x samples, RP, RP/BP, and WO3 after 6 h of visible light irradiation. (e) Interface-assisted catalytic C-C Coupling of Au singleatoms over RP. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to ethane. Reproduced with promission. (f) Photocatalytic activity of Au1/RP in CO2 reduction reaction, TOF for photocatalytic CO2 reduction of Au1/RP in comparison with recent reports. The production yield rates (g-h). Reproduced with promission. (a and b) are adapted with permission from ref. 111 (Copyright 2024, Elsevier); (c-e) are reproduced with permission from ref. 216 (Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society); and (f-h) are reproduced with permission from ref.217 (Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society). |

Fig. 12 (a) Mechanism of photocatalytic bacterial inactivation. (b) Photocatalytic inactivation performance and the corresponding spread plate results against S. aureus. (c) Mechanism of photocatalytic bacterial inactivation. (d) Inactivation of E.coli and corresponding spread plate results. (e) Sterilization mechanism of the RPNPs under simulated sunlight. (f)The antibacterial efficiency of RPNPs under different conditions. (a and b) are adapted with permission from ref. 233 (Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society); (c and d) are reproduced with permission from ref. 113 (Copyright 2019, Elsevier); and (e and f) are reproduced with permission from ref. 234 (Copyright 2021, Elsevier). |

(Fig. 12e-f) [234].

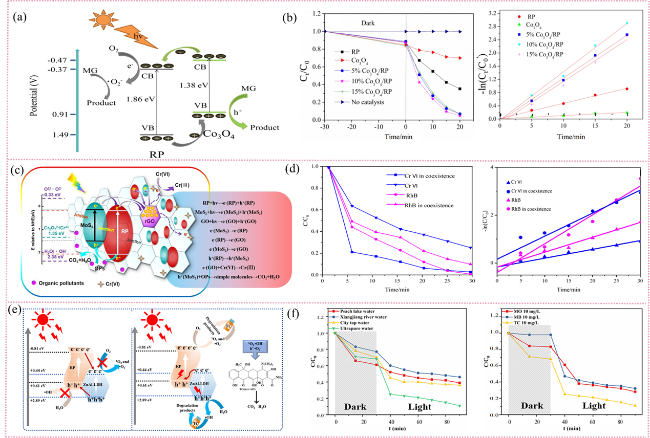

6.4 Photocatalytic pollutant degradation

Fig. 13 (a) Photocatalytic degradation mechanism diagram. (b) Degradation efficiency and kinetics of MG under visible light using various photocatalysts. (c) Photocatalytic degradation mechanism diagram. (d) Photocatalytic performance for Cr(VI) reduction and RhB oxidation under varying conditions, with corresponding kinetic fitting. (e) Photocatalytic degradation mechanism diagram (f) Degradation efficiency in natural water samples and other organic pollutants. (a and b) are adapted with permission from ref. 263 (Copyright 2020, Elsevier); (c and d) are reproduced with permission from ref. 264 (Copyright 2018, Elsevier); and (e and f) are reproduced with permission from ref. 87 (Copyright 2023, Elsevier). |

6.5 Other photocatalytic applications

6.5.1 Nitrogen fixation

6.5.2 Photoelectrochemical (PEC) sensing

6.5.3 Resource extraction and separation technology

7 Challenges in current research

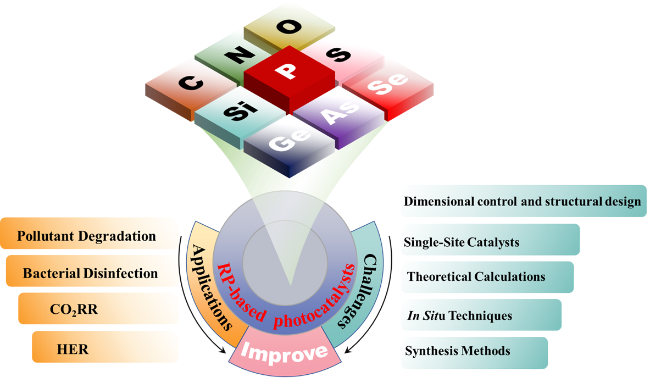

Fig. 14 Summary and perspective for RP-based photocatalysts. |