1. Introduction

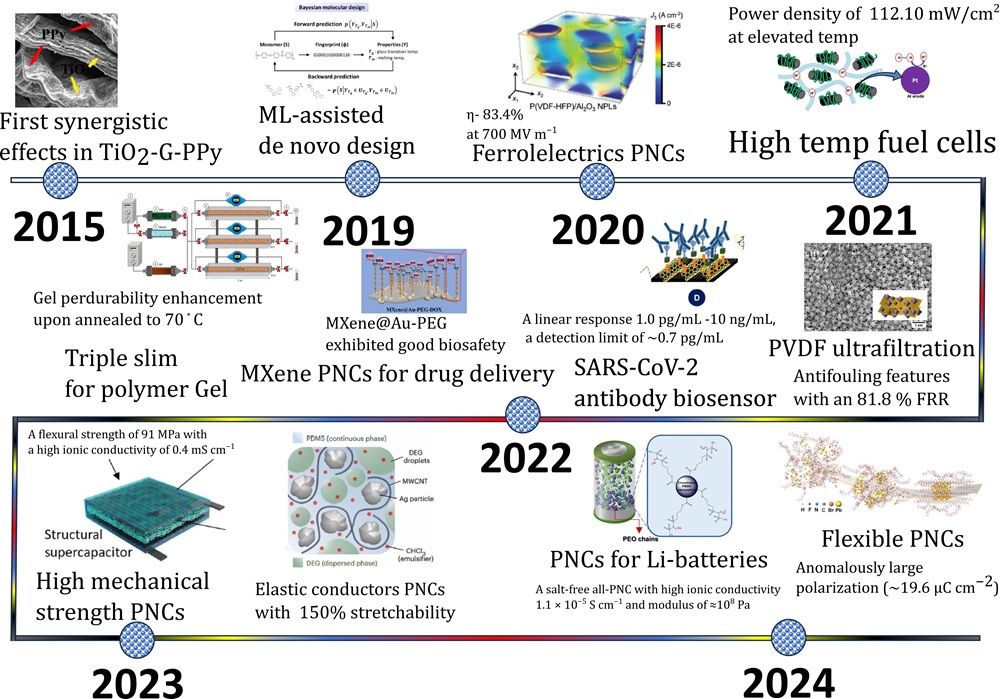

Fig.1. Overview of the PNCs in the last decade. |

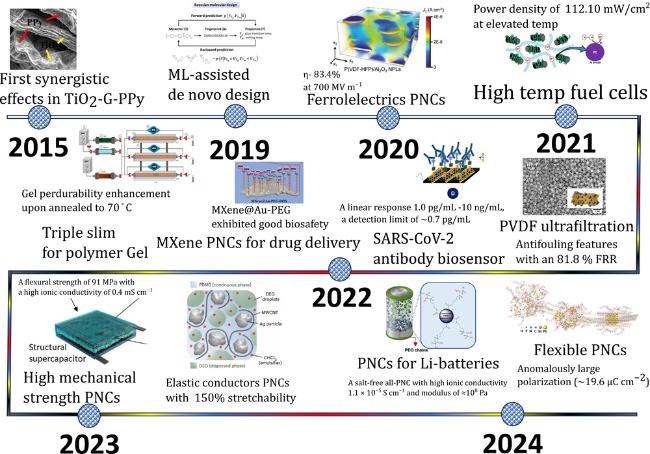

Fig. 2. The overview of synthetic methods, advanced characterization, and physicochemical properties of PNCs. |

2. Chemical and Physical Properties of PNCs

Table 1. Comparison: PNCs vs. Conventional Polymer Composites |

| Feature | PNCs | Conventional PNCs |

|---|---|---|

| Filler Size | 1-100 nm (NPs) | >1 µm (micro- or macro-fillers) |

| Filler Distribution | Uniform (better dispersion) | Often uneven (agglomeration issues) |

| Mechanical Properties | High strength, toughness, and flexibility | Moderate improvement over pure polymers |

| Thermal Stability | Higher due to nanofiller-polymer interactions | Limited enhancement |

| Electrical & Optical Properties | Enhanced conductivity, transparency, and optical properties | Limited conductivity and optical tuning |

| Barrier Properties | High resistance to gas, moisture, and chemicals | Moderate barrier performance |

| Processing Complexity | Advanced dispersion techniques | Easier to process |

| Cost | Generally higher | More cost-effective |

| Applications | Advanced fields: electronics, biomedical, aerospace | Traditional applications: automotive, construction |

3. Synthesis Routes and Fabrication of PNCs

3.1 DFT calculations

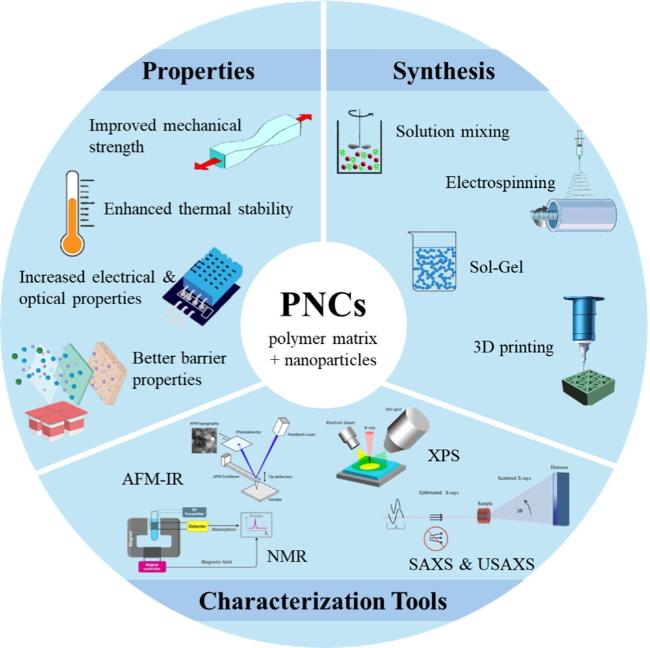

Fig. 3. DFT of PNCs for energy applications. (a) Microstructural diagram of PNCs with random NPs, (b) Vertical nanofibers, (c-f) Corresponding breakdown paths under different applied electric fields, (g, h) The distributions of the local electric field (i, j) Schematic outline of electron avalanche modes in respective cases, reproduced with permission from Ref.[38], copyright © 2025 Springer Nature.; (k) Illustration of PLA-GN-MCC/PANI composites, (l) Core-shell structure of PLA-GN-MCC/PANI composites, (m) Schematic representation of hydrogen bonding in the PLA-GN-MCC/PANI molecular structure model, reproduced with permission from Ref.[45], copyright © 2023 Elsevier Ltd; (n, o) Snapshot of poly-AM adsorbed on the MMT surface after 3.0 ns of MD simulations at 275 K, 50 MPa, reproduced with permission from Ref.[46], copyright © 2023 Royal Society of Chemistry. |

Table 2. ANOVA for Response Surface Quadratic Model[55] |

| Source | Sum of square | df | Mean square | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| model | 1.689×105 | 14 | 12,062.42 | 108.15 | <0.0001 |

| A | 85,323.38 | 1 | 85,323.38 | 764.97 | <0.0001 |

| B | 0.375 | 1 | 0.375 | 0.0034 | 0.9545 |

| C | 5192.04 | 1 | 5192.04 | 46.55 | <0.0001 |

| D | 64,170.04 | 1 | 64,170.04 | 575.32 | <0.0001 |

| AB | 18.06 | 1 | 18.06 | 0.1619 | 0.6931 |

| AC | 798.06 | 1 | 798.06 | 7.16 | 0.0173 |

| AD | 27.56 | 1 | 27.55 | 0.2471 | 0.6263 |

| BC | 18.06 | 1 | 18.06 | 0.1619 | 0.6931 |

| BD | 390.06 | 1 | 390.06 | 3.5 | 0.0811 |

| CD | 217.56 | 1 | 217.56 | 1.95 | 0.1829 |

| residual | 1673.08 | 15 | 111.54 | - | - |

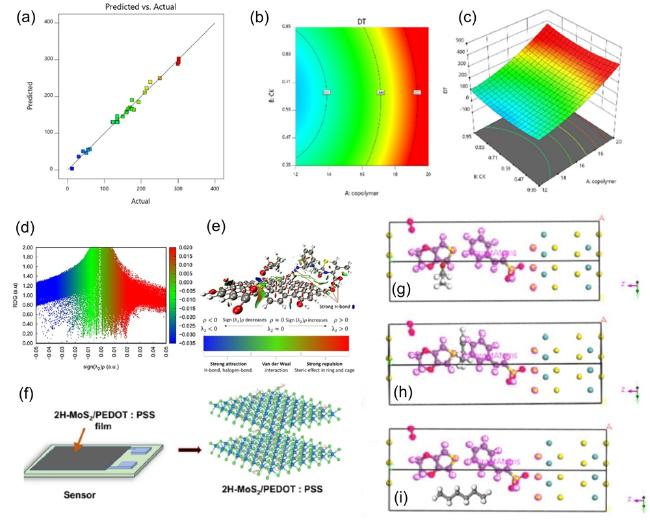

Fig. 4. DFT of PNCs for petroleum, biomedical, and sensing applications. (a) Comparison between predicted and actual value of gel degradation time. Blue to red indicates a degradation time of 12~301 h, (b, c) 3D surface plots and contour plots between degradation time revealed the interactions between copolymer and crosslinker, reproduced with permission from Ref.[67], copyright © 2024 ACS Publication; (d) RDG isosurface map of noncovalent interactions of GO/PEG−CEX composites, (e) The optimized geometric structure outlining where the color bar associated to different interaction outcome, reproduced with permission from Ref.[60], copyright © 2022 ACS Publication; (f) schematic of MoS2-PEDOT:PSS sensor devices and the corresponding composite layered structures, (g) propanol, (h) toluene, and (i) hexane on an oxygen pre-adsorbed EDOT:SS/MoS2 (002) substrate, reproduced with permission from Ref.[68], copyright © 2024 ACS Publication. |

4. Characterization Tools

4.1 In Situ Characterizations

4.1.1 High-Resolution TEM

4.1.2 In Situ Scanning Electron Microscopy

4.1.3 Atomic Force Microscopy-Infrared Spectroscopy

4.1.4 Small, Wide, and Ultra-small Angle X-ray scattering

4.1.5 X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy with Depth Profiling

4.1.6 Neutron Scattering Techniques

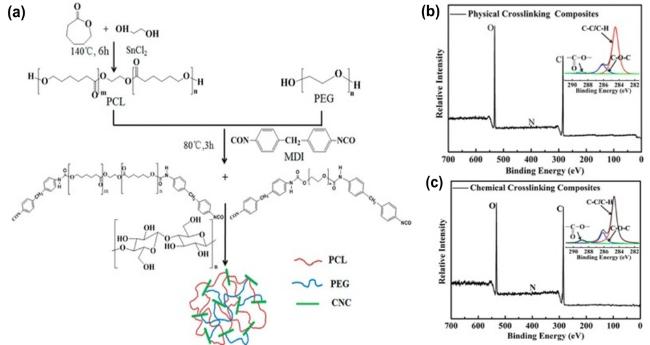

Fig. 5. Shape memory process of PEG-PCL-CNC thermo-responsive nanocomposite. (a) The scheme showing the synthetic route for the PEG-PCL-CNC nanocomposite. XPS survey spectra of the (b) physically cross-linked nanocomposite and (c) chemically cross-linked nanocomposite PEG(60)-PCL(40)-CNC(10). Figs. (a) - (c) reproduced with permission from Ref.[104] Copyright © 2015 American Chemical Society. |

4.2 Ex-situ Characterizations

4.2.1 Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

4.2.2 Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy

4.2.3 Raman Imaging & Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (TERS)

4.2.4 Positron Annihilation Lifetime Spectroscopy (PALS)

4.2.5 Gas Chromatography

Table 3. Representative Characterization Techniques for PNCs: Categories, Principles, and Applications |

| Technique | Category | Principle | Key Applications in PNCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| XRD | X-ray-Based | Diffraction pattern analysis of crystalline structures | Phase identification, crystallinity assessment, structural defects |

| XPS | X-ray-Based | Surface chemical analysis using photoelectron emission | Elemental composition, chemical bonding, interfacial interactions |

| AFM-IR | Optical-Based | Nanoscale IR absorption mapping | Chemical composition, filler dispersion, polymer crystallinity |

| SEM | Optical-Based | High-resolution electron imaging | Surface morphology, dispersion of nanofillers, and phase distribution |

| TEM | Optical-Based | Electron beam transmission imaging at the nanoscale | Nanofiller morphology, interface interaction, and crystallinity |

| Raman Imaging | Optical-Based | Raman scattering with enhanced spatial resolution | Molecular structure, stress distribution, polymer-filler interactions |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Optical-Based | Light absorption in the UV and visible regions | Optical properties, bandgap analysis, NP stability |

5. Emerging PNC Applications

5.1 Energy Sectors

5.1.1 Fuel Cells

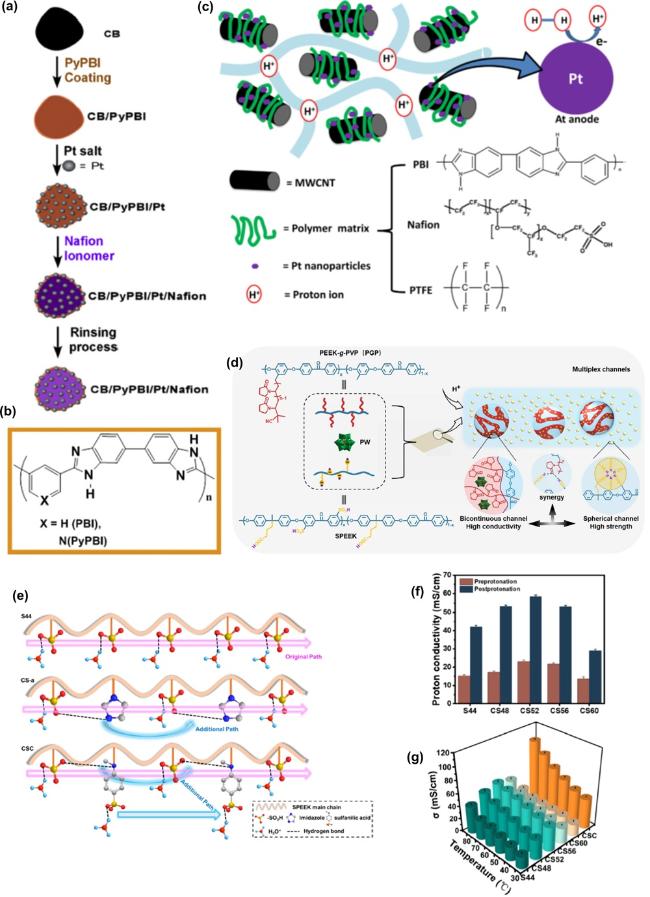

Fig. 6. Current progress and research trends in PNC for fuel cells applications. (a) Configuration of double-coating layers of polymers on CB. (b) Corresponding chemical structures used (poly[2, 20-(2, 6-pyridine)-5, 50-bibenzimidazole] (PyPBI) and Nafioin. Figs. (a) - (b) reproduced with permission from Ref.[154], Copyright © 2018 Elsevier Ltd.; (c) The interaction mechanism of polymer with MWCNT, reproduced with permission from Ref.[155], Copyright © 2020 Elsevier Ltd.; (d) The nanocomposite PEEK-g-PVP membranes strategy equipped by multiplex proton transport channels, reproduced with permission from Ref.[156], Copyright © 2023 Elsevier Ltd.; (e) Illustration of the proton transfer mechanism of sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) (SPEEK) with sulfonation degree of 44% (top), imidazole groups (middle), and comb-shaped (bottom) membranes. (f) Proton conductivity of the functionalized SPEEK membranes before and after protonation at 80 °C.; (g) Membranes’ proton conductivity at various temperatures. Figs. (e) - (g) reproduced with permission from Ref.[163], Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society. |

5.1.2 Solar Cells

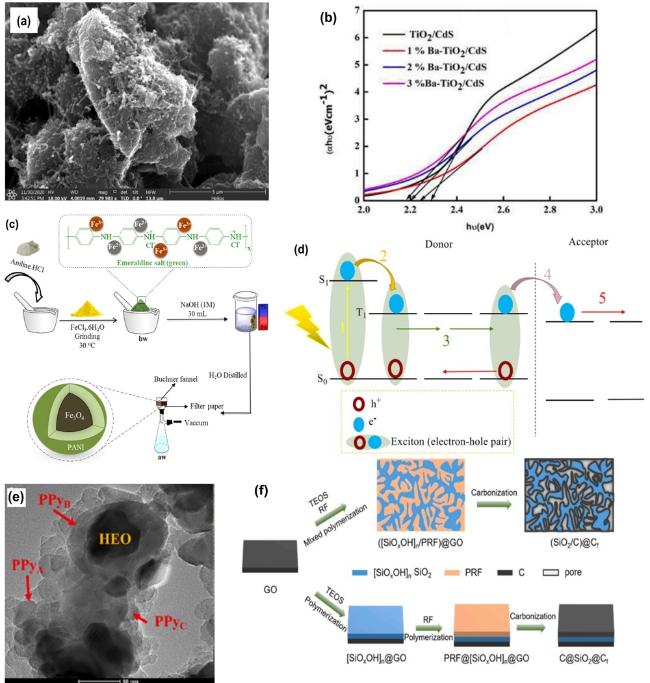

Fig. 7. (a) Distribution of MWCNTs throughout the PTh matrix, reproduced with permission from Ref.[191], copyright © 2022 Elsevier Ltd.; (b) Tauc plots of 1%-3% barium doped TiO2/CdS, reproduced with permission from Ref.[206], copyright © 2022 Elsevier Ltd.; (c) Schematic drawing of the synthesis of superparamagnetic nanocomposites, (d) Schematic energy diagram of a heterojunction photovoltaic cell based on the conversion of singlet excitons into triplet excitons to an increased effective diffusion length of the photogenerated excitons, where the numbering refers to: 1) Photon absorption, 2) Singlet to triplet transition, 3) Triplet to triplet transition, 4) Electron transfer, 5) Charge transport, Figs. (c-d) reproduced with permission from Ref. [214] copyright © 2020 Elsevier Ltd.; (e) TEM images of the HEO@PPy nanocomposites, reproduced with permission from Ref.[215], copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V.; (f) Schematic illustration of two different routes to (SiO2/C)@Cf and C@SiO2@Cf.; (f) reproduced with permission from Ref.[216], copyright © 2023 Elsevier B.V. |

5.1.3 Lithium-ion Batteries (LIBs)

5.1.4 Supercapacitors

5.2 In situ hydrogel nanocomposites in upstream oil and gas sector

5.2.1 Effect of Nanomaterials on Gelation Time of PNCs Gels

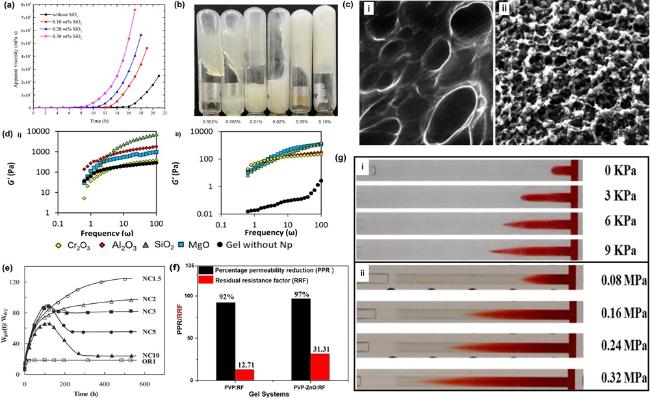

Fig. 8. (a) Viscosity changes of gelling solutions with different SiO2 concentration, reproduced with permission from Ref.[269], copyright © 2017 American Chemical Society; (b) Gelation of HPAM/PEI gels with different SiO2 concentration, reproduced with permission from Ref.[270], copyright © 2023 Elsevier B.V.; (c) ESEM image of gels i) with and ii) without SiO2 NPs, reproduced with permission from Ref.[280], copyright © 2017 The Japan Petroleum Institute; (d) G’ of nanocomposite gels with different NPs at polymer concentrations of i) 8000 mg/L and ii) 4000 mg/L, reproduced with permission from Ref.[275], copyright © 2019 MDPI ; (e) Swelling behavior of Nanocomposite NCn, n corresponds to the concentration of clay (Conc = n × 10-2 mol/L), reproduced with permission from Ref.[281], copyright © 2011 American Chemical Society; (f) Percentage Permeability Reduction (PPR) and Residual Resistance Factor (RRF) of PVP/RF gels with and without ZnO NPs, reproduced with permission from Ref.[273], copyright © 2021 IFP Energies nouvelles; (g) Rupture process of PG i) without and ii) with 2% nanosilica, reproduced with permission from Ref.[282], copyright © 2024 The Royal Society of Chemistry. |

5.2.2 Effect of Nanomaterials on PG Strength and Rheology

5.2.3 Effect of Nanomaterials Swelling Behavior of PNCs Gels

5.2.4 Effect of Nanomaterials on Plugging Ability of PNCs Gels

5.3 Environmental Remediation

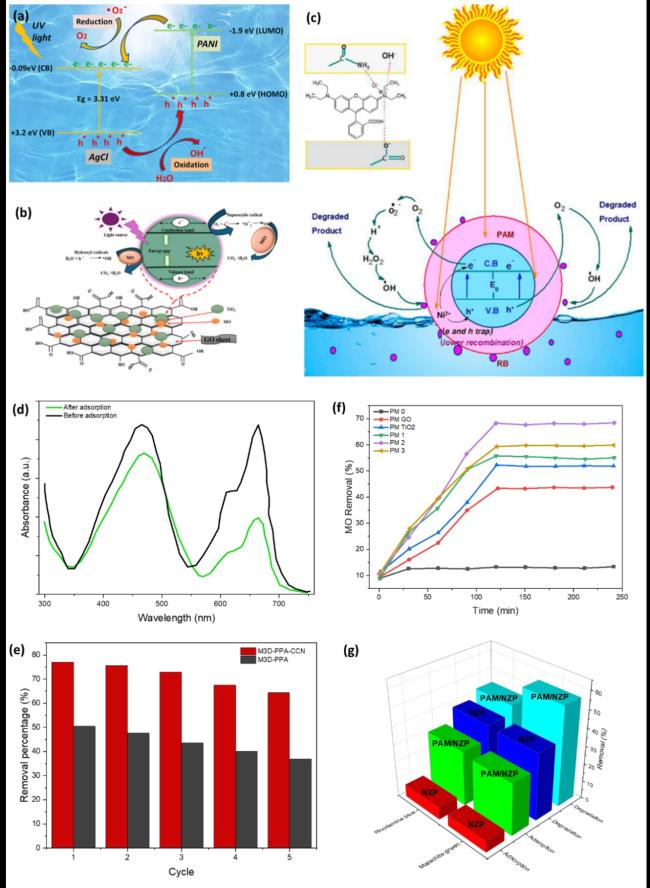

5.3.1 The role of PNCs in Wastewater Treatment Technology and Water Purification

5.3.2 Working Mechanism of PNCs in Wastewater Treatment

5.3.3 Towards high-efficiency of PNCs in Treating Wastewater

Fig. 9. Photocatalytic and adsorption mechanisms for dye removal: (a) AgCl@PANI-4% nanocomposite for organic dye degradation, reproduced with permission from Ref.[316], copyright © 2023 Elsevier B.V. (b) TiO2-GO membrane for MO, reproduced with permission from Ref.[207], copyright © 2024 Springer Nature. (c) PAM/NZP for toxic dye removal, reproduced with permission from Ref.[317], copyright © 2014 American Chemical Society. Comparative performance: (d) UV-Vis spectra of MB and MO adsorption by M3D-PAA-CCN, (e) removal efficiency over five cycles, (d), (e) reproduced with permission from Ref.[328] (f) MO photodegradation by membranes, reproduced with permission from Ref.[207], copyright © 2024 Springer Nature. and (g) MG and RB removal by NZP and PAM/NZP under dark and sunlight conditions, reproduced with permission from Ref.[317], copyright © 2014 American Chemical Society. |

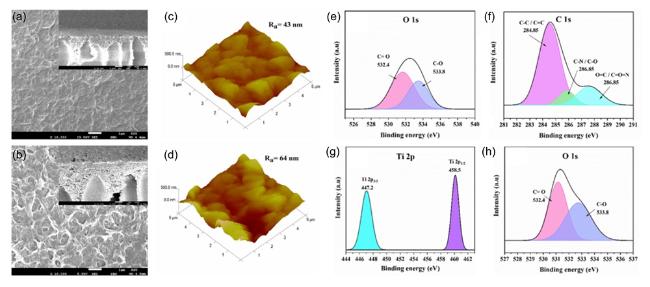

5.3.4 Surface Properties of PNCs for Wastewater Treatment

Fig. 10. Surface characterization of PNCs: FE-SEM (a) TFN and (b) TFC, insets show the cross-sectional imaging of the respective case; AFM images (c) TFN and (d) TFC; XPS spectra showing (e) O 1s and (f) C 1s for TFC, and (g) Ti 2p and (h) O 1s for TFN with 80 ppm TiO2 NSs. Figs. (a)-(h) reproduced with permission from Ref.[336], copyright © 2024 MDPI. |

5.4 Biomedical Applications

5.4.1 Drug Delivery

Fig. 11. (a) Drug release profiles of 5-FU from LBG-g-PAcM-2 and LBG-g-PAcM-SN2 under acidic (pH 1.2) and (b) neutral (pH 7.4) conditions. Figs. (a)-(b) reproduced with permission from Ref.[368], copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V. In vivo study on the therapeutic efficacy of Ag NPs@HA/DOX in a HELA-xenograft mouse model: (c) Tumor progression at 7 and 14 days under different treatments, and (d) Tail morphology of treated mice on day 14. Figs. (c)-(d) reproduced with permission from Ref.[369], copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V. Bone regeneration in a rat cranial defect model treated with PCL/Col/ZIF-8 composite membrane: (e) 3D micro-CT reconstructions showing bone repair after 8 weeks, (f) Bone volume to tissue volume quantification, and (g) Bone mineral density (BMD) measurement. Fig (e)-(g) reproduced with permission from Ref.[370], copyright © 2021 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. MRI study on CPNiNP for glioblastoma imaging: Biodistribution showing accumulation in the (h) orthotopic model in the tumor and contralateral healthy brain, and (i) heterotopic model in the liver, renal cortex, renal medulla, and tumor. (j) T2W brain images post-injection with red arrows marking tumor localization. Figs. (h)-(j) reproduced with permission from Ref.[371], copyright © 2021 MDPI. Effect of SANHs in a full-thickness skin defect in a diabetic mice model: (k) Wound size on the backs of mice after various treatments, and (l) Wound closure rate following different treatments. In vitro antibacterial efficiency of SANHs: (m) Surface antibacterial activity on E. coli, (n) SEM images of E. coli morphology post-treatment, and (o) Quantification of antibacterial effect. Figs. (k)-(o) reproduced with permission from Ref.[372], copyright © 2023 Dove Medical Press Ltd. |

5.4.2 Tissue Engineering

5.4.3 Biomedical Imaging

5.4.4 Wound Healing

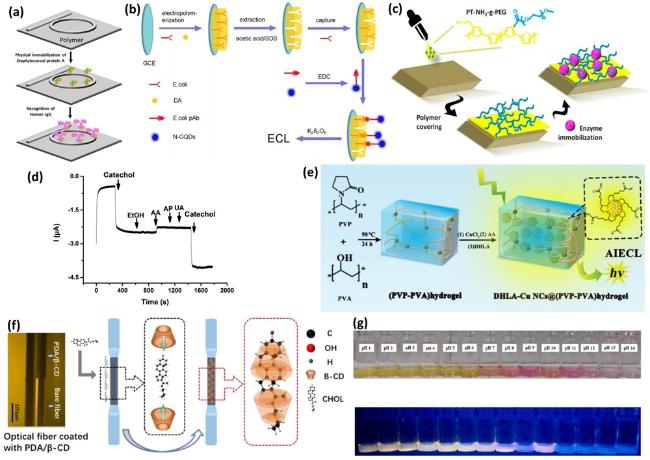

5.5 Chemical and Biosensor Applications

Fig. 12. (a) Schematic detection of proteins, reproduced with permission from Ref.[434], copyright © 2012 American Chemical Society. (b) Schematic detection of E. coli, reproduced with permission from Ref.[427], copyright © 2017 American Chemical Society. (c) Schematic detection of lateral amino groups. (d) Sensitivity of electrochemical sensor. Figs. (c)-(d) reproduced with permission from Ref.[435], copyright © 2015 American Chemical Society. (e) Schematic detection of microRNA, reproduced with permission from Ref.[436], copyright © 2023 American Chemical Society. (f) Schematic detection of cholesterol, reproduced with permission from Ref.[437], copyright © 2023 Elsevier B.V. (g) Optical image of fluorometric biosensors, reproduced with permission from Ref.[438], copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V. |

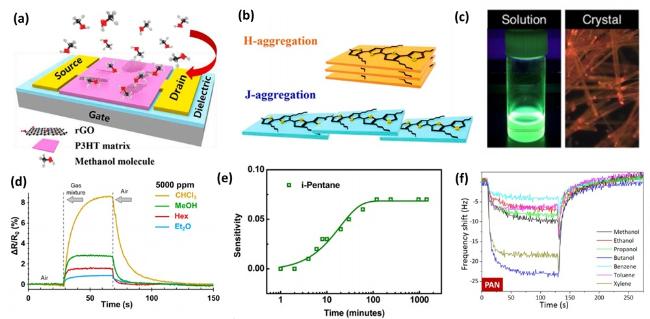

Fig. 13. (a) Structure of OFET sensor based on photo-irradiated P3HT/rGO composite film. (b) Schematics of H and J aggregate structures of P3HT. Figs. (a)-(b) reproduced with permission from Ref.[455], copyright © 2021 Elsevier B.V. (c) Photographs of the CHCl3 solution and crystals of β-COPV under UV-light illumination at 365 nm, reproduced with permission from Ref.[456], copyright © 2021 American Chemical Society. (d) Resistance responsivity of the TPU−(TPU/CB)−TPU structure upon exposure to 5000 ppm of four different VOCs (chloroform, methanol, hexanes, and ethanol) with arrows and vertical dashed lines indicating exposure to VOC and air, reproduced with permission from Ref.[457], copyright © 2019 American Chemical Society. (e) Sensitivity of P3HT/PCBM to VOCs of i-pentane, reproduced with permission from Ref.[458], copyright © 2013 American Chemical Society. (f) Full-cycle dynamic responses of the QCM sensors functionalized with thin films under the influence of various VOCs at a concentration of 1 mg/L, reproduced with permission from Ref.[459], copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society. |

Table 4. Composite polymer-based sensors for gas and VOCs detections |

| Polymer | Mixing compounds | Detection methods | Analyte | Sensitivity | Limit of Detection | Response | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAA | Alginate | EC | Hydrogen peroxide | 71.9 mA/(cm2mM) | 0.9 mM | n.a | [466] |

| Commercial polymer BAYHYDROL-110 | Metglas 2826 MBA (Fe40Ni38Mo4B18) | Magnetoelastics | P-xylenes O-xylenes | −1.87 kHz per % concentration −2.72 kHz per % concentration | ~260 ppm ~180 ppm | n.a | [467] |

| PANI PPy Poly-3-methylthiophene (P3MT) | Heteropolyacids of Keggin | EC | Alcohol Acetone Benzene Xylene Toluene Chloroform | n.a | n.a | ~3 s ~3 s ~3 s ~3 s ~3 s ~3 s | [432] |

| Poly(p-xylylene) (PPx) Poly(4-hexyloxy-2,5-biphenylene-ethylene) (PHBPE) | 10- camphorsulfonic acid (CSA) | EC | x-chloromethane | n.a | n.a | 5 × 10−5 s | [468] |

| PVDF PPy | 2D-Bi2S3 | Electrical signals (I-V signals) | Temperature Pressure Strain | −0.1117°C−1 (TCR) >1.51 kPa−1 45.4 (GF) | 24°C 1 kPa n.a | 0.33 s 0.04 s 0.1 s | [469] |

| Polyepichlorohydrin (PECH) Polyisobutylene (PIB) Polybutadiene (PBD) | acoustic wave exposure Acoustic wave exposure Acoustic wave exposure | Electrical signals (I-V signals) Electrical signals (I-V signals) Electrical signals (I-V signals) | Methyl ethyl ketone Hexane Chloroform Toluene Methyl ethyl ketone Hexane Chloroform Toluene Methyl ethyl ketone Hexane Chloroform Toluene | n.a | 25 ppm 460 ppm 41 ppm 8 ppm 258 ppm 60 ppm 102 ppm 11 ppm 72 ppm 59 ppm 34 ppm 7 ppm | n.a | [470] |

| Polystyrene (PS) | Carbon black (CB), diethylene glycol dibenzoate (DEGDB) | Electrical signals (I-V signals) | Ethanol 2-propanol Acetone Heptane Benzene Toluene Ethylbenzene | 14.3 (%/%) 13.6 (%/%) 12.6 (%/%) 10.5 (%/%) 6.7 (%/%) 3.6 (%/%) 1.8 (%/%) | 973.1 ppm 597.8 ppm 253.8 ppm 86.1 ppm 47.9 ppm 34.2 ppm 27.2 ppm | ~100 s ~100 s ~100 s 400 s 400 s 400 s 400 s | [471] |

| PVA | Graphite | EC | Methanol | 2 mM | 126 μmol dm−3 | 3.3 μmol dm−3 | [472] |

| P3HT | Quartz crystal microbalance electrodes (QCM) | EC | 3-methyl-1-butanol 1-hexanol | 25-500 ppm | 4.35 ppm 3.20 ppm | 1.54 ppm | [406] |

| Fluorosiloxane | - | Optical detection | Alcohol Hexane Benzene Toluene | n.a | 8.3 μg | ~10 s ~18 s ~15 s ~21 s | [473] |

| Low density polyethylene (LDPE) | Nitrile butadiene rubber (NBR) | Gas diffusion on LDPE | Hydrogen Helium Nitrogen Oxygen Argon | n.a 70.8 x 10-11 m2/s 2.42 x 10-11 m2/s 4.27 x 10-11 m2/s 3.39 x 10-11 m2/s | n.a | n.a | [474] |

| PPy NPs | - | Interdigitated microelectrode array | Ammonia | 1.7 - 5.4 % | 5 ppm | < 1s | [475] |

| PPy NPs | - | UHF-RFID | Ammonia | 25 ppm | 0.1 ppm | ~600 s | [476] |

| PAA and PVP | Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) | Photoionization detector | Isoprophyl alcohol | ~ 0.3 | 100 ppm | < 2 min | [477] |

| Polydiacetylene (PDA) | Silica aerogel | Colorimetric and fluorescence analysis | Benzene Acetone Toluene | 100 ppm | n.a | n.a | [478] |

| PEDOT, Poly(styrene sulfonic acid) (PSS) | MoS2 | EC. | Ethanol | 56.9 % | 500 ppm | 8.2 s | [479] |

| Poly(N-vinylcarbazole) (PVK) | Cellulose acetate | Pressure and Fluorometric analysis | Toluene 1-butanol Acetone Dichoromethane | 3.79 kPa 0.89 kPa 30.61 kPa 57.98 kPa | n.a | n.a | [480] |

| PDMS | - | Holographic gratings in polymeric matrices | Hydrocarbon vapours | 9 - 99.5 % concentration | n.a | < 1 s | [481] |

| Si Silastic T4 Plyurethane Techsil F42 PVA | Nickel | Chemiresistive | Ethanol Hexane THF Ethanol Hexane THF Ethanol Hexane THF | 6.3 >7.5 x 108 6.3 x 103 1.2 x 106 >4.5 x 104 >1 x 107 >4.8 x 108 1.6 >3.3 x 104 | n.a n.a ~100 ppm n.a n.a ~100 ppm n.a n.a n. | ~60 s ~10 s <10 s ~60 s ~10 s <10 s n.a n.a n.a | [482],[483] |

| Poly (3-dodecylthiophene) PDDT Pth-PANI) P3HT | QCM | EC | P-xylene | n.a | ~200 ppm | ~2 s <20 s <15 s | [484] |

| P3HT | rGO | EC | Methanol Ethanol Isopropyl alcohol Acetone | n.a n.a n.a n.a | 1 ppm 1 ppm 1 ppm 1 ppm | 42 s 50 s 46 s 44 s | [455] |

| Poly(2-acrylamido-2-methyl-1-propanesulfonic acid) (PAMPSA) N-3-(dimethylamino)-propyl methacrylamide (DMAPMAm) and methoxyethyl methacrylate (MEMA) (PD-co-M), and diethylamine (DEA) (PDMD) | - - | Chemiresistive Chemiresistive | Ammonia Carbondioxides Ammonia Carbondioxides | 16.2 % >2 x 104 ppm >10-1 >2 x 104 ppm | 0.05 ppm 0.05 ppm | n.a n.a | [485] |

6. Challenges, future directions, and outlooks

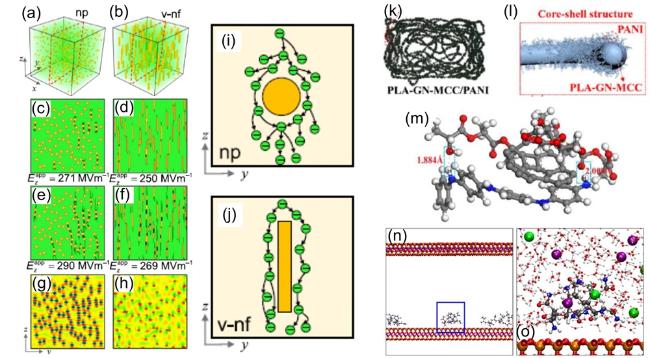

Fig. 14. Summary and future prospect of PNCs in diverse applications. |